In this week’s parsha, Moshe proves he’s ahead of his time, most strikingly in the first question he asks when he starts addressing Hashem.

When Hashem calls to Moshe from the bush, Moshe responds with “Here I am,” hineni. In Hebrew, it’s one word, one concept, הנני מוכן ומזומן–I’m here and I’m ready. Not just presence, it’s total presence.

But what’s the next thing Moshe says? Hashem first tells him all about the plan, that Moshe’s going to go to Paroh, going to bring out bnei Yisrael. And suddenly, Moshe isn’t so sure. What does he say? “Who am I?” מי אנוכי / mi anochi? He thought he knew, but now all of a sudden… he isn’t so sure.

Which of us haven’t been there? In that spot where we thought we were brave, we stepped up, put up our hands, applied to make aliyah or signed up for grad school. Whatever it was, we are about to take that leap, and then suddenly, we wonder. Is this the right thing to do? Is this really who I am?

This is actually a very modern question. Throughout most of our history, we didn’t need to ask who we were. Wherever we lived, Poland, Morocco, Egypt, Spain, everybody around us was all too happy to answer: “You’re a Jew.” “You can live in these places, you can do these occupations, you can pay these taxes.” They were happy to show us the fences around our Jewish identity and inside those, we were Jews.

That doesn’t mean we always got along. Chassidim and mitnagdim, Ashkenazim and Sephardim, more observant and less observant. In Europe, different professions had their own shuls: carpenters didn’t want to daven with candlemakers, or whatever. There were always lines we put ourselves on one side of or the other. But whether or not to be a Jew—that wasn’t a choice, or rather, non-Jews made the choice for us.

Then, all of a sudden, for those of us in Europe, there was. With the Enlightenment, there was the promise of no more fences. After thousands of years, we could ask, Mi anochi? We could be whoever we wanted to be. Things went wrong in Europe, but they kept trying in America, building on the idea that nobody could tell you what it meant to be a Jew.

“Who am I?” we asked. Mi anochi? There were so many answers: Zionists, Reform, Orthodox, modern Orthodox, feminists, fighters for civil rights, Buddhists. The one thing most of us didn’t much didn’t want to be? Just a Jew. Nobody wanted to get back into that box.

And it worked. According to a Pew survey released in 2013, there are now half the Jews in America than in the 1950s. But the biggest change is that out of everyone who said they were Jewish, 22% said they had no religion. In most religions, this would be an oxymoron, but you know exactly what I’m talking about. And that 22% is not across the board. Very few Jews born before 1945 say they have no religion, while almost one-third of millennials do, people who were born after 1980.

Mi anochi? If you’re a postmodern Jew, you can be anything, but “Jew” is nowhere near the top of the list. A Jewish day school in Toronto had an ad campaign a while ago featuring kids dressed up as adults: the ads read “Future Doctor,” “Future Lawyer,” I forget what else. But none said Future Rabbi. And none said Future Jew. The choice to be a Jew is so unappealing we don’t even mention it to our kids. Maybe we’re scared to admit it’s a choice, but that’s a mistake, because for a Jew, it’s absolutely the best choice.

Here, when Moshe asks about his identity, Mi anochi, Hashem has a strange answer. Moshe asks,

מִי אָנֹכִי, כִּי אֵלֵךְ אֶל-פַּרְעֹה; וְכִי אוֹצִיא אֶת-בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל, מִמִּצְרָיִם.

“Who am I, that I should go unto Pharaoh, and that I should bring forth the children of Israel out of Egypt?”

Most of the meforshim, like the Ramban, see this as a comparison: “Who am I, a little shepherd, compared to the great king?” Here’s what Hashem responds:

כִּי-אֶהְיֶה עִמָּךְ, וְזֶה-לְּךָ הָאוֹת, כִּי אָנֹכִי שְׁלַחְתִּיךָ:

“Certainly I will be with you; and this shall be the sign for you, that I have sent you.”

Most people figure Hashem is saying, “Don’t worry, forget about comparing yourself, I’m on your side so it’s okay.” And that’s very powerful, but Moshe could probably have figured that out on his own.

What if Moshe is asking seriously? He truly doesn’t fit in anywhere. Wherever he goes, other people define him: to the Mitzriyim, he’s an Ivri, to the Midyanim, he’s a Mitzri. So he’s not only asking about himself compared to Paroh—a shepherd versus a king—he’s also asking, “What kind of Jew am I, an ignoramus, raised among goyim?” It’s the quintessential modern question: where do we fit in among our family, community, nation, people? Given all this, why doesn’t Hashem seem to offer a serious response?

As parents, we know what happens if we don’t give our kids good answers. They keep asking. They’re scared of monsters under the bed, we say it’ll be okay, and two minutes later, they’re scared again because we didn’t give them any proof, it was just empty words. Of course their doubts come back again.

But Moshe doesn’t ask again. Somewhere in Hashem’s words, Moshe really has gotten his answer. So maybe if we look closely at what Hashem tells him, we can also find an answer for ourselves, modern Jews who, no matter who we are or where, ask these same questions all the time.

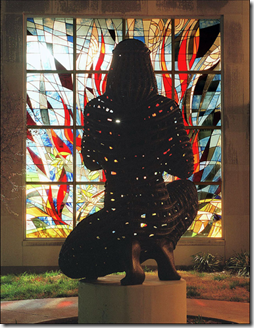

(Image © Richard Simon via Wikimedia)

Looking for answers, I found that most people take the Ramban’s approach, that Moshe is asking about his worthiness. So I was excited to see that Rabbi Jonathan Sacks picks up on this nuance as well. In his exploration of Shemos two years ago, he wrote, “But there is another question within the question. ‘Who am I?’ can be not just a question about worthiness. It can also be a question about identity.” Thank you, Rabbi Sacks!

Rabbi Sacks explains that Moshe is asking about himself as a Jew who is uninvolved in his Jewish identity. He wasn’t enslaved like the rest, he had no place in the community. And of course, the one time he tried to step in and stop two Jews from fighting, things didn’t go well. They rejected his claim to what we’d call today Jewish authenticity. So Moshe’s pretty sure he doesn’t have much of a future as a Jew.

But look what’s happening here: the bush continues to burn, and Moshe is still standing there. He’s still asking, Mi anochi? He doesn’t turn around and leave.

Rabbi Sacks writes, “There are Jews who believe and those who don’t. There are Jews who practise and those who don’t. But there are few Jews indeed who, when their people are suffering, can walk away saying, ‘This has nothing to do with me.’”

Deep inside, Moshe knows it has everything to do with him, even if nobody else sees it. And just like Rabbi Sacks says, he can’t walk away. That’s why he killed the Mitzri police officer; that’s why he stopped the two Jews fighting. Those stories prove to us and to Hashem what Moshe still can’t see—he belongs, even if he’s still questioning his identity.

That’s Hashem’s answer: even if the questions are hard, I’ll be with you while you work it out. And perhaps that’s also the sign Hashem mentions, why He’s sent us—to wrestle with these hard questions of identity all over again in each generation.

This week was my birthday—and my father’s 10th yahrzeit. I can’t believe it’s been a decade without him.

This week, 49 years ago, I was born and given the most beautiful name my mother could think of: Jennifer. And then, I guess a few days later, my father made his way to shul and gave me my Hebrew name, for their relatives: Yosefa for her uncle Joseph, Miriam for his aunt Mary. And then, 40-something years later, I made my way to Israel and chose yet another name for myself, Tzivia, my great-grandmother’s name, a name that I have made my own.

And I think the lesson we can all learn from the example of Moshe Rabbeinu in this week’s parsha, and from my father, who took on and learned so much about Judaism and about himself, constantly challenging himself and growing, right to the very end of his life, is that we don’t have to be afraid of the hard questions. Hashem chooses us davka because of the hard questions. And we don’t have to be afraid to change, to embrace new visions for ourselves as we learn and grow.

Is this who I am? Maybe not yet. Maybe it can be.

Who am I? Mi anochi? It’s a question that takes a lifetime to answer, an answer that evolves over our lifetimes, but that’s okay with Hashem and we have to learn to let that be okay with us. Identity isn’t fixed at birth, and it’s not fixed in adulthood either. All the major milestones: marriage, giving birth, burying loved ones; they all change who we are in one way or another. Throughout our lives, our identity changes and hopefully it grows and enriches our own lives and the lives of everyone else around us.

It’s a lot like Har Sinai, where we’re told that Bnei Yisrael responded with Naaseh, we’ll do it, before adding, Nishma, and we’ll also try to understand it, wrestle with it, grapple with it. We don’t walk away. We stand and face that burning bush – hineni, I’m here Hashem, do with me what you want. And by the way, Hashem, Mi anochi? Who am I? Show me the way you want me to grow.

And Hashem’s answer to Moshe begins to make sense, because what he’s saying is, “Good for you for sticking around. Good for you for asking. You’ve passed the test. You’ve got this.”

I’m paraphrasing.

It has now been a decade with my father, and I realized a few days ago that it’s been a decade in which I reached so many goals for myself: I became a published author, I moved to Israel, I finished my Master’s degree. I’m a tough act to follow, but I have no doubt that I will, that there’s even more to me than this. Stick around and find out. May the next decade be one of growth, of learning, of exploration.

May it be a decade where we blow ourselves away with all the different kinds of Jew, all the different kinds of person, we can be. As long as the bush still burns, there’s no limit to the wonderful possibilities.

The image above is a lovely combination of a sculpture by Eldon Teft (some sites spell his name Tefft) and a stained glass window designed by Charles Marshall that appear at the entrance to University of Kansas religious studies building Smith Hall. Here’s another view of the sculpture itself, which is intricate bronze and larger than life:

(© Patrick Emerson, via Flickr.)

Here’s another good image of this thrilling combination of art that isn’t allowed to be shared. And another. :-)

And as a special treat, I’ll leave you Leonard Cohen’s very dark but very fitting song “Hineni,” which I might have shared here before, and which was released just a few weeks before his death. It features the choir of the synagogue where he grew up in Montreal. (Oops, it’s not CALLED Hineni, it’s called “You want it darker.” But pretend, just for now, that it IS called Hineni, so it kind of fits what I’ve been saying here…)

Comments

Post a Comment

I love your comments!