NOTE: One year after my brother Eli's death in 2014, I published a book about the intertwining of our lives and his struggle with schizophrenia. This post and many other writings are included, in slightly different form, in that book.

Please wait until the ride has come to a full and complete stop is now available in print and Kindle editions.

Through laughter and tears, I invite you to come share my final journey with my brother.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In light of the school shooting on Friday in Connecticut, a mother has released a heartfelt article saying, “I am sharing this story because I am Adam Lanza's [Friday’s shooter’s] mother. I am Dylan Klebold's and Eric Harris's mother. I am Jason Holmes's mother. I am Jared Loughner's mother. I am Seung-Hui Cho's mother. And these boys—and their mothers—need help. In the wake of another horrific national tragedy, it's easy to talk about guns. But it's time to talk about mental illness.”

In light of the school shooting on Friday in Connecticut, a mother has released a heartfelt article saying, “I am sharing this story because I am Adam Lanza's [Friday’s shooter’s] mother. I am Dylan Klebold's and Eric Harris's mother. I am Jason Holmes's mother. I am Jared Loughner's mother. I am Seung-Hui Cho's mother. And these boys—and their mothers—need help. In the wake of another horrific national tragedy, it's easy to talk about guns. But it's time to talk about mental illness.”

So let’s talk.

Let’s talk about my family’s Chanukah party, which often sucks anyway, because our father continues to be dead (yes, we’re grown-ups, and yes, it’s been four years, but still). What semblance of a party there was last week, thanks to my mother’s very hard work, was totally shattered by the wandering-in and shouting and carrying-on of my possibly drunk but definitely crazy, smelly, bedraggled little brother.

He’s never been violent, but boy… last week was the closest. He came here a few times, and it was the first time, after 18 years of mental illness, that I thought he might actually hurt somebody. Ted had to ask him to leave, and in the end, he did. Same thing at the party; my mother eventually shut and locked the door. He came back in a couple of times, quietly at first but getting louder each time until eventually he left for good.

I will emphasize: he didn’t hurt anybody. I don’t think he ever would. Sometimes, his gentleness amazes me, because I don’t know what demons he’s wrestling with. I hate to throw a cliché like that in there – demons (shudder) – but there it is. I don’t know what he’s struggling with, but sometimes it doesn’t seem like he’s struggling hard enough. He’s sure as heck not winning and neither was our party.

Which is not the same as shooting school kids. This morning, he called while I was in the other room and told Naomi, “don’t tell your mother I called.” She DID tell me, and I assured her that she shouldn’t have secrets from parents “unless it’s something little and happy, like a birthday present.” But even telling her that – it’s more naughtiness than anything else.

So my brother doesn’t hurt anybody… unless you count the family members who have no idea how to keep him safe, and how to protect the rest of us from his shouting, irrational, scary behaviour.

The mother who wrote the article, Liza Long, doesn’t want her son put in jail for his violent, antisocial behaviour. “No one wants to send a 13-year-old genius who loves Harry Potter and his snuggle animal collection to jail.” But there are no other options left.

In the paternalistic atmosphere of former times, people were often institutionalized for years – for life. Trouble was, sometimes they were actually sane. Sometimes, they had treatable problems. And these days, the thinking goes, we have amazing medical solutions that can fix almost everything; even better! Fix em up, out the door, save a fortune!

So the institutions have gone the way of the tuberculosis sanatorium and instead we look for ways to integrate such people into our community – supportive housing, shelters, and… well, the fine arrangement my brother has settled on since the summer: living under a bridge. Except the underside of bridges can get a little cold here in Canada ‘round about December time.

Most of our lives, we were inseparable. Growing up 17 months apart, I thought we were two halves of the same person. Me and my “dark twin.” He quickly caught up to me, somehow; he was bigger, stronger, smarter as long as I could remember. He was in French immersion, so I learned French. I remember rolling my tongue, savouring the word “violon” he’d taught me, singing Nana Mouskouri’s “haricots dans les oreilles” song. We’d curl up under the sheets and pretend we were twins, waiting to be born. We’d switch clothing and try to trick everybody – nobody was ever fooled. We finished each other’s sentences, read each other’s mind, used deaf-blind sign language on each other’s palms in synagogue.

Most of our lives, we were inseparable. Growing up 17 months apart, I thought we were two halves of the same person. Me and my “dark twin.” He quickly caught up to me, somehow; he was bigger, stronger, smarter as long as I could remember. He was in French immersion, so I learned French. I remember rolling my tongue, savouring the word “violon” he’d taught me, singing Nana Mouskouri’s “haricots dans les oreilles” song. We’d curl up under the sheets and pretend we were twins, waiting to be born. We’d switch clothing and try to trick everybody – nobody was ever fooled. We finished each other’s sentences, read each other’s mind, used deaf-blind sign language on each other’s palms in synagogue.

Except he was way, way smarter; he won math contests and entered science fairs, talked physics problems on the phone with his friend Nima (not at Princeton, probably well on his way to a Nobel), played the violin and piano, really played, when I’d dropped out after a couple of miserable years. And he used to brag to people that I was a writer; I slept with a dictionary beside my bed – he was proud of me in the same way I was proud of him.

It is hard to remember that he used to be a person, giving and taking, like regular people do.

Not that Eli was ever quite a regular person. Irregularities started showing through pretty early, probably before junior high school. He cut his bangs with hedge trimmers. He wore a hat for a whole year in school, an inappropriately woolly toque. He didn’t shave his facial hair for years after it started coming in, preferring to live in denial. And when we’d take a bus together, we’d be talking normally at the bus stop, but then he’d tell me he was going to pretend to have Tourette’s. I had no idea what that was, but knew I should sit far, far away, so I did, watching him babbling or talking nonsense to people on the bus and chalking it up to the regular embarrassment of teenagerhood; isn’t every preteen girl utterly embarrassed by her brother? Oh, he also spent a year of university living in a car, dropped out of a co-op placement… well, the list goes on and on.

Looking back, it all fits together. It’s easy to see that he went off the rails long before his first admission. My mother says he used to say there was something wrong with his eyes; things just LOOKED funny. She took him to the ophthalmologist whenever he’d say that; they never found anything wrong. To this day, he has perfect vision. And things still look funny.

Months before his first admission, after he graduated from university (Bachelor of Math; double major, applied math and pure math, graduating average well over 96%), I had a baby and got a teaching job a couple of weeks later. Eli was unemployed, deschooled; the perfect candidate for the task of part-time babysitter. He was still reliable enough to show up every day and watch the baby. They had a good time together. He snuggled, kept track of the pacifier, fed the baby the right stuff, reported to me about the baby’s routine.

I forget why he stopped, but right around then was when he started calling my 80-something-year-old bubby in the middle of the night to ask her what he should do with his life. And then he was hospitalized for the first time.

This week, he eventually came so unhinged, maybe from being off his meds and wandering, maybe from being frozen and underfed, that he was finally “ill enough” to admit to a (euphemistically-named) “mental health” institution for a bit of warmth. He called today – he thinks they may discharge him this week. Of course, like anybody else, he doesn’t like being in an hospital and is looking forward to living on his own again.

What can we do about all of this? Absolutely nothing.

Oh, my mother does tons of stuff. She makes sure the government doesn’t cut off his disability or health care (it’s free, but you need an address; you need to renew it, with a photo, every few years). She makes dental appointments and ensures he keeps them (he lost his front teeth a few years ago in an accident he doesn’t remember, but my parents bought him implants, finding a very patient and gentle dentist he would trust). She asks if he’s on his meds. She coordinates with the person at the community treatment centre. She pays the shelters when he’s spent his government cheque on alcohol or necklaces or radios; did I mention he’s crazy?

What else does my mother do for him?

She yells at the manager of the cheque-cashing place because they gave him a “payday” loan at some usurious rate of interest because he was sane enough, for three minutes, to sign the promissory note. She arranged subsidized housing, but his place got filthy and he started leaving burners on when he went out – bugs and filth and fire risk go against the terms of their contract, and they don’t have a place for him anymore. At one point, she and my father were talking about buying a condo for him somewhere and sending in a maid – a solution which could never be viable; the dirt is just so far beyond messiness that no cleaning staff would deal with it. Zookeepers, maybe.

My 41-year-old little brother could be a full-time job if my mother wanted one; at 67, she doesn’t particularly, but carries on anyway, because nobody else can. If she ever can’t anymore – well, he’ll wind up living under a bridge, drunk and dirty, which is often how he winds up anyway.

Here’s what I do: absolutely nothing. If he shows up at my door and he’s polite, I offer what I might to a stranger: food, a place to sit in the warmth (on the stairs, not the furniture; I’m terrified of bedbugs), coffee or tea (this summer, he accepted instant coffee and stirred it into iced tea; yum!), use of the phone. If I’m in the mood, I chat. If not, I don’t – I tell myself he doesn’t notice either way. If he calls and he’s polite, I’ll listen for a minute. There is no give and take, no conversation. Eventually, I tell him I have to go.

Usually, I’m annoyed, if not angry. I’m not as kind as I could be – that’s my sisters’ specialty, especially Sara, who is so kind to him and everybody, but then I worry that the whole world is going to eventually break her heart when people are stupid and unkind, as they often are. To my sisters, he’s the broken big brother in perhaps the same way that I’m the curmudgeonly frum big sister; an odd gravitational force to navigate around and not get sucked into.

Mostly, I wish he’d go away. Last week, after the disasters at the Chanukah party, I wondered for a while how I felt about this brother of mine, and what I felt was mostly angry, annoyance, wishing he’d go away. The brother I grew up with is gone for good. And I don’t want the one I do have. Closure would be nice; death would be easier than this annoying smelly inconvenient person. Quicker. Terrible, terrible thoughts.

And then the mood passes and I’m okay, and I’m friendly the next time he calls – and luckily, he doesn’t call that often because then I might dissolve into annoyance and anger once again.

Have I talked enough? Have we solved the problems yet?

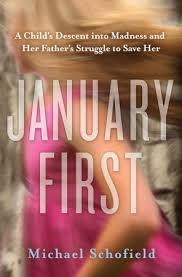

I read a book recently called January First that I would recommend if you want to know about mental illness – the real, scary extremes. Rarely do I find a book as upsetting as this one was, even though this was NOT my experience of my parents’. More typical is a diagnosis in the early or mid-20s, which is when my brother was diagnosed. The girl in this book, January (but her parents call her Jani), was diagnosed very young; I think maybe three or four. And she’s dangerous; not just ordinary little-kid dangerous, but so dangerous that her parents have to get separate apartments so she won’t kill her little brother. (read an excerpt here to decide if you’re interested and up to reading the full story)

I read a book recently called January First that I would recommend if you want to know about mental illness – the real, scary extremes. Rarely do I find a book as upsetting as this one was, even though this was NOT my experience of my parents’. More typical is a diagnosis in the early or mid-20s, which is when my brother was diagnosed. The girl in this book, January (but her parents call her Jani), was diagnosed very young; I think maybe three or four. And she’s dangerous; not just ordinary little-kid dangerous, but so dangerous that her parents have to get separate apartments so she won’t kill her little brother. (read an excerpt here to decide if you’re interested and up to reading the full story)

The most disturbing thing about this book, for me, is the very incompleteness of the story. As he wrote it, his daughter was still a child, as she still is today. There is no happy ending; there is no ending at all. As with any of our stories – as with ALL of our stories, the ending has yet to be written. It’s a metaphor and yet it is also so very true.

I read a blog post a while ago by a woman in Israel (found it! Click here to read) who had somewhat befriended a homeless non-Jewish man who lived nearby. When he was in good shape, he could do odd jobs around her home and she’d give him food. When he wasn’t, I guess he’d just go away for a while, lose touch, and then, eventually come back. Except eventually, he died, and she blogged about him and how he’d touched her life, and I thought, “that is not the worst thing in the world.”

To be a gentle homeless person with a few connections to the world, to have a few people who care about you, to eventually die of something – I don’t know what exactly (dwelling on it ruins the fond haziness of imagining); well, it’s not the worst ending.

Ultimately, unlike many illnesses, the ending is not in our hands or the doctors’… it’s in his own incompetent, filthy palms. We’ve already had a sneak preview of some of the grand possibilities in the Choose-Your-Own-Adventure that is Life with Severe Mental Illness: disfiguring, potentially-fatal bike accident – check! criminal activity – check! drugs (maybe not) but slow suicide by alcohol – check! talking to messed-up strangers in ways they might interpret as picking a fight – check!

Most of the choices are equally bad, and I’m never getting my brother back. I think I’ve talked enough for now. Maybe it’s someone else’s turn.

Please wait until the ride has come to a full and complete stop is now available in print and Kindle editions.

Through laughter and tears, I invite you to come share my final journey with my brother.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In light of the school shooting on Friday in Connecticut, a mother has released a heartfelt article saying, “I am sharing this story because I am Adam Lanza's [Friday’s shooter’s] mother. I am Dylan Klebold's and Eric Harris's mother. I am Jason Holmes's mother. I am Jared Loughner's mother. I am Seung-Hui Cho's mother. And these boys—and their mothers—need help. In the wake of another horrific national tragedy, it's easy to talk about guns. But it's time to talk about mental illness.”

In light of the school shooting on Friday in Connecticut, a mother has released a heartfelt article saying, “I am sharing this story because I am Adam Lanza's [Friday’s shooter’s] mother. I am Dylan Klebold's and Eric Harris's mother. I am Jason Holmes's mother. I am Jared Loughner's mother. I am Seung-Hui Cho's mother. And these boys—and their mothers—need help. In the wake of another horrific national tragedy, it's easy to talk about guns. But it's time to talk about mental illness.”So let’s talk.

Let’s talk about my family’s Chanukah party, which often sucks anyway, because our father continues to be dead (yes, we’re grown-ups, and yes, it’s been four years, but still). What semblance of a party there was last week, thanks to my mother’s very hard work, was totally shattered by the wandering-in and shouting and carrying-on of my possibly drunk but definitely crazy, smelly, bedraggled little brother.

He’s never been violent, but boy… last week was the closest. He came here a few times, and it was the first time, after 18 years of mental illness, that I thought he might actually hurt somebody. Ted had to ask him to leave, and in the end, he did. Same thing at the party; my mother eventually shut and locked the door. He came back in a couple of times, quietly at first but getting louder each time until eventually he left for good.

I will emphasize: he didn’t hurt anybody. I don’t think he ever would. Sometimes, his gentleness amazes me, because I don’t know what demons he’s wrestling with. I hate to throw a cliché like that in there – demons (shudder) – but there it is. I don’t know what he’s struggling with, but sometimes it doesn’t seem like he’s struggling hard enough. He’s sure as heck not winning and neither was our party.

Which is not the same as shooting school kids. This morning, he called while I was in the other room and told Naomi, “don’t tell your mother I called.” She DID tell me, and I assured her that she shouldn’t have secrets from parents “unless it’s something little and happy, like a birthday present.” But even telling her that – it’s more naughtiness than anything else.

So my brother doesn’t hurt anybody… unless you count the family members who have no idea how to keep him safe, and how to protect the rest of us from his shouting, irrational, scary behaviour.

The mother who wrote the article, Liza Long, doesn’t want her son put in jail for his violent, antisocial behaviour. “No one wants to send a 13-year-old genius who loves Harry Potter and his snuggle animal collection to jail.” But there are no other options left.

In the paternalistic atmosphere of former times, people were often institutionalized for years – for life. Trouble was, sometimes they were actually sane. Sometimes, they had treatable problems. And these days, the thinking goes, we have amazing medical solutions that can fix almost everything; even better! Fix em up, out the door, save a fortune!

So the institutions have gone the way of the tuberculosis sanatorium and instead we look for ways to integrate such people into our community – supportive housing, shelters, and… well, the fine arrangement my brother has settled on since the summer: living under a bridge. Except the underside of bridges can get a little cold here in Canada ‘round about December time.

Most of our lives, we were inseparable. Growing up 17 months apart, I thought we were two halves of the same person. Me and my “dark twin.” He quickly caught up to me, somehow; he was bigger, stronger, smarter as long as I could remember. He was in French immersion, so I learned French. I remember rolling my tongue, savouring the word “violon” he’d taught me, singing Nana Mouskouri’s “haricots dans les oreilles” song. We’d curl up under the sheets and pretend we were twins, waiting to be born. We’d switch clothing and try to trick everybody – nobody was ever fooled. We finished each other’s sentences, read each other’s mind, used deaf-blind sign language on each other’s palms in synagogue.

Most of our lives, we were inseparable. Growing up 17 months apart, I thought we were two halves of the same person. Me and my “dark twin.” He quickly caught up to me, somehow; he was bigger, stronger, smarter as long as I could remember. He was in French immersion, so I learned French. I remember rolling my tongue, savouring the word “violon” he’d taught me, singing Nana Mouskouri’s “haricots dans les oreilles” song. We’d curl up under the sheets and pretend we were twins, waiting to be born. We’d switch clothing and try to trick everybody – nobody was ever fooled. We finished each other’s sentences, read each other’s mind, used deaf-blind sign language on each other’s palms in synagogue. Except he was way, way smarter; he won math contests and entered science fairs, talked physics problems on the phone with his friend Nima (not at Princeton, probably well on his way to a Nobel), played the violin and piano, really played, when I’d dropped out after a couple of miserable years. And he used to brag to people that I was a writer; I slept with a dictionary beside my bed – he was proud of me in the same way I was proud of him.

It is hard to remember that he used to be a person, giving and taking, like regular people do.

Not that Eli was ever quite a regular person. Irregularities started showing through pretty early, probably before junior high school. He cut his bangs with hedge trimmers. He wore a hat for a whole year in school, an inappropriately woolly toque. He didn’t shave his facial hair for years after it started coming in, preferring to live in denial. And when we’d take a bus together, we’d be talking normally at the bus stop, but then he’d tell me he was going to pretend to have Tourette’s. I had no idea what that was, but knew I should sit far, far away, so I did, watching him babbling or talking nonsense to people on the bus and chalking it up to the regular embarrassment of teenagerhood; isn’t every preteen girl utterly embarrassed by her brother? Oh, he also spent a year of university living in a car, dropped out of a co-op placement… well, the list goes on and on.

Looking back, it all fits together. It’s easy to see that he went off the rails long before his first admission. My mother says he used to say there was something wrong with his eyes; things just LOOKED funny. She took him to the ophthalmologist whenever he’d say that; they never found anything wrong. To this day, he has perfect vision. And things still look funny.

Months before his first admission, after he graduated from university (Bachelor of Math; double major, applied math and pure math, graduating average well over 96%), I had a baby and got a teaching job a couple of weeks later. Eli was unemployed, deschooled; the perfect candidate for the task of part-time babysitter. He was still reliable enough to show up every day and watch the baby. They had a good time together. He snuggled, kept track of the pacifier, fed the baby the right stuff, reported to me about the baby’s routine.

I forget why he stopped, but right around then was when he started calling my 80-something-year-old bubby in the middle of the night to ask her what he should do with his life. And then he was hospitalized for the first time.

This week, he eventually came so unhinged, maybe from being off his meds and wandering, maybe from being frozen and underfed, that he was finally “ill enough” to admit to a (euphemistically-named) “mental health” institution for a bit of warmth. He called today – he thinks they may discharge him this week. Of course, like anybody else, he doesn’t like being in an hospital and is looking forward to living on his own again.

What can we do about all of this? Absolutely nothing.

Oh, my mother does tons of stuff. She makes sure the government doesn’t cut off his disability or health care (it’s free, but you need an address; you need to renew it, with a photo, every few years). She makes dental appointments and ensures he keeps them (he lost his front teeth a few years ago in an accident he doesn’t remember, but my parents bought him implants, finding a very patient and gentle dentist he would trust). She asks if he’s on his meds. She coordinates with the person at the community treatment centre. She pays the shelters when he’s spent his government cheque on alcohol or necklaces or radios; did I mention he’s crazy?

What else does my mother do for him?

She yells at the manager of the cheque-cashing place because they gave him a “payday” loan at some usurious rate of interest because he was sane enough, for three minutes, to sign the promissory note. She arranged subsidized housing, but his place got filthy and he started leaving burners on when he went out – bugs and filth and fire risk go against the terms of their contract, and they don’t have a place for him anymore. At one point, she and my father were talking about buying a condo for him somewhere and sending in a maid – a solution which could never be viable; the dirt is just so far beyond messiness that no cleaning staff would deal with it. Zookeepers, maybe.

My 41-year-old little brother could be a full-time job if my mother wanted one; at 67, she doesn’t particularly, but carries on anyway, because nobody else can. If she ever can’t anymore – well, he’ll wind up living under a bridge, drunk and dirty, which is often how he winds up anyway.

Here’s what I do: absolutely nothing. If he shows up at my door and he’s polite, I offer what I might to a stranger: food, a place to sit in the warmth (on the stairs, not the furniture; I’m terrified of bedbugs), coffee or tea (this summer, he accepted instant coffee and stirred it into iced tea; yum!), use of the phone. If I’m in the mood, I chat. If not, I don’t – I tell myself he doesn’t notice either way. If he calls and he’s polite, I’ll listen for a minute. There is no give and take, no conversation. Eventually, I tell him I have to go.

Usually, I’m annoyed, if not angry. I’m not as kind as I could be – that’s my sisters’ specialty, especially Sara, who is so kind to him and everybody, but then I worry that the whole world is going to eventually break her heart when people are stupid and unkind, as they often are. To my sisters, he’s the broken big brother in perhaps the same way that I’m the curmudgeonly frum big sister; an odd gravitational force to navigate around and not get sucked into.

Mostly, I wish he’d go away. Last week, after the disasters at the Chanukah party, I wondered for a while how I felt about this brother of mine, and what I felt was mostly angry, annoyance, wishing he’d go away. The brother I grew up with is gone for good. And I don’t want the one I do have. Closure would be nice; death would be easier than this annoying smelly inconvenient person. Quicker. Terrible, terrible thoughts.

And then the mood passes and I’m okay, and I’m friendly the next time he calls – and luckily, he doesn’t call that often because then I might dissolve into annoyance and anger once again.

Have I talked enough? Have we solved the problems yet?

The most disturbing thing about this book, for me, is the very incompleteness of the story. As he wrote it, his daughter was still a child, as she still is today. There is no happy ending; there is no ending at all. As with any of our stories – as with ALL of our stories, the ending has yet to be written. It’s a metaphor and yet it is also so very true.

I read a blog post a while ago by a woman in Israel (found it! Click here to read) who had somewhat befriended a homeless non-Jewish man who lived nearby. When he was in good shape, he could do odd jobs around her home and she’d give him food. When he wasn’t, I guess he’d just go away for a while, lose touch, and then, eventually come back. Except eventually, he died, and she blogged about him and how he’d touched her life, and I thought, “that is not the worst thing in the world.”

To be a gentle homeless person with a few connections to the world, to have a few people who care about you, to eventually die of something – I don’t know what exactly (dwelling on it ruins the fond haziness of imagining); well, it’s not the worst ending.

Ultimately, unlike many illnesses, the ending is not in our hands or the doctors’… it’s in his own incompetent, filthy palms. We’ve already had a sneak preview of some of the grand possibilities in the Choose-Your-Own-Adventure that is Life with Severe Mental Illness: disfiguring, potentially-fatal bike accident – check! criminal activity – check! drugs (maybe not) but slow suicide by alcohol – check! talking to messed-up strangers in ways they might interpret as picking a fight – check!

Most of the choices are equally bad, and I’m never getting my brother back. I think I’ve talked enough for now. Maybe it’s someone else’s turn.

I don't know if it helps anyway, but I read that he has been able to consolidate the two apartments and finally live with both kids. I bought the book to show support for them, but I don't know if I will read it.

ReplyDeleteI just happened upon your blog and your entries entiled "Eli" today... a year after his death. My sister went to Waterloo with him first year, and he made quite an impression on both of us. So much so that we named our kitty Eli and my Eli lived to be 18 and died in 2013. I thought about Eli Lapell often, as I said the name Eli forty times a day as my kitty was a sprightly smart stubborn Aquarius just like his namesake. My sister (Anne Marie) thought of your Eli constantly over the years and only found out he was dead too late. My mom even remembers him fondly, as he'd biked to Hamilton and showed up on her doorstep one day, asking if he could sleep in her backyard. My mom (sprightly stubborn Aquarius herself) joined him out there and they laid on the grass, this sixty something mom and Eli, then in his 20s, staring at the stars and talking about the universe. She said he was gone in the morning, didn't even want breakfast or a blanket, but she remembered that night fondly and thought the world of him.

ReplyDeletePlease know that despite his decline in later years, he was loved and fondly remembered and made a VERY big impression on those of us who knew him too briefly in the early 90s.

Jo,

DeleteThank you so much for your wonderful words. Thanks for sharing these memories... I love hearing other people's stories about Eli, and hope to discover more of them as time passes.

Rest assured that Eli was cherished and appreciated even within our own family. Last month, I turned some of the love and some of the tears into a book, which includes this post, in edited form, along with many others from my blog, along with new and original writing. I invite you and anyone who loved him to share the book and honour his memory: Please wait until the ride has come to a full and complete stop.